By Natasha Kabanda

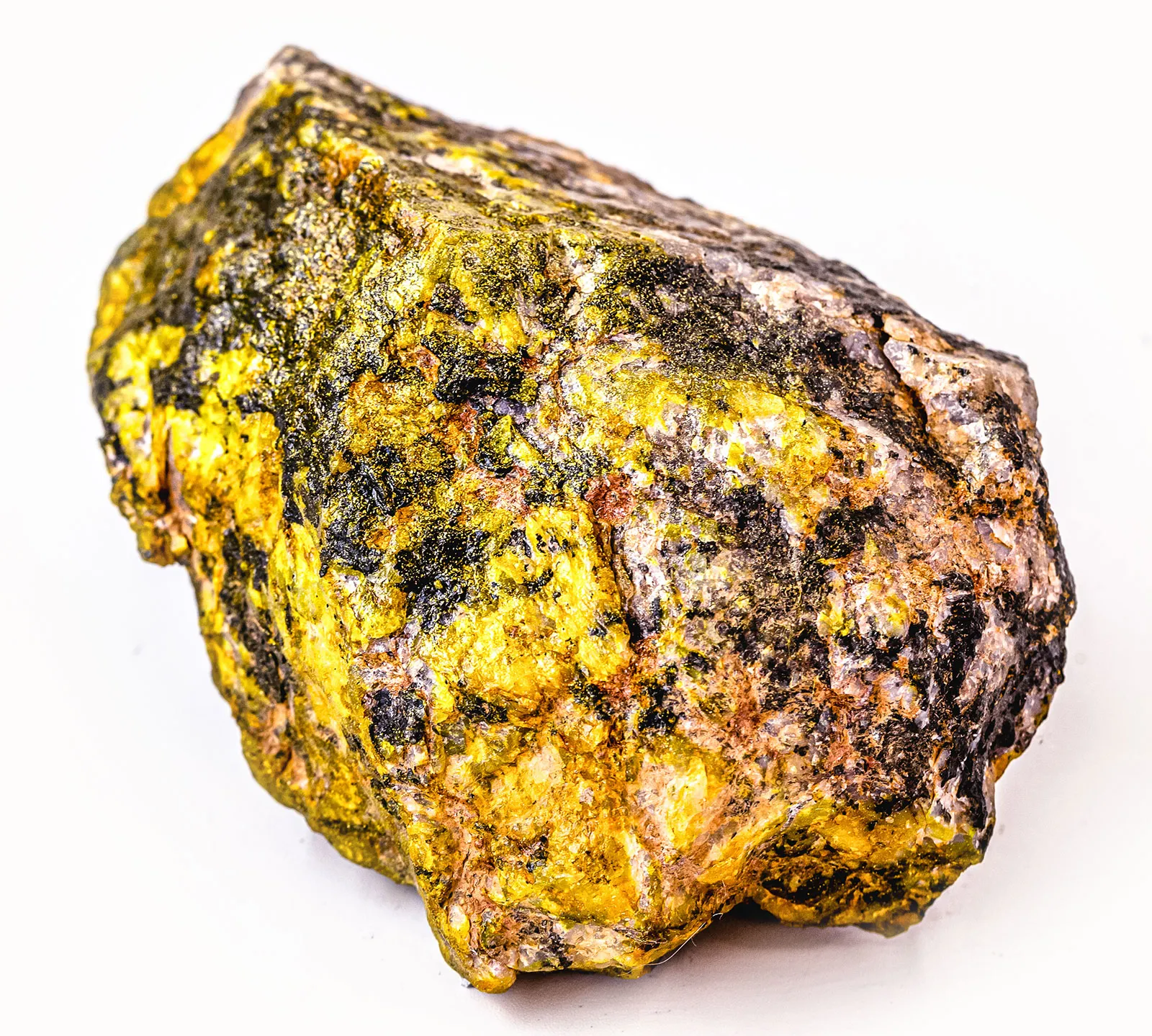

Zambia’s mineral wealth has long been a cornerstone of its economy. From copper to cobalt, gold, and gemstones, mining continues to be a key driver of national growth. For decades, the nation has been recognised for its vast copper reserves, which have attracted multinational investments and generated considerable export revenue. Now, as the world pivots toward cleaner energy and strategic minerals, Zambia finds itself in the sights of international investors not just for its traditional resources but increasingly for uranium. With global energy markets shifting toward nuclear and renewable power, uranium is being redefined as a critical mineral for the future.

One project that exemplifies this shift is the proposed Muntanga Uranium Project, spearheaded by GoviEx Uranium Zambia Limited, a subsidiary of the Canadian-based GoviEx Uranium Inc. If developed, this initiative could become one of Zambia’s few uranium mining ventures, signalling a new chapter in the country’s extractive industry. The project has sparked significant public interest, not only for the economic opportunities it promises, such as job creation and increased foreign direct investment, but also for the environmental and social considerations it raises. As Zambia navigates this new terrain, the Muntanga project may serve as a litmus test for how the country balances mineral development with sustainable and inclusive growth.

Amid ongoing discussions around investment, job creation, and economic diversification, it is essential to pause and reflect. While mining can offer growth opportunities, it does not automatically translate into equitable or sustainable development. The Muntanga Uranium Project highlights the complexity of Zambia’s evolving path, entering new territory in both environmental and governance dimensions. If not carefully managed, this project could lead to ecological degradation, social disruption, and regulatory challenges. A thoughtful, inclusive approach is necessary to ensure that the benefits are broadly shared and long-term risks are minimised.

The Muntanga Uranium Project is scheduled to begin operations in 2028. It is expected to run for 25 years, during which more than 33 million pounds of uranium oxide (U₃O₈) could be extracted from the area. While this offers clear economic potential, the proposed mine sits near Lake Kariba, one of Southern Africa’s most important sources of freshwater, fisheries, and biodiversity. For nearby communities, this lake is more than a body of water; it is a source of life, culture, and livelihood.

Mining near such a sensitive ecosystem requires more than promises of development. It requires clear safeguards, inclusive decision-making, and ongoing accountability to ensure that both people and nature are protected, not just during the mine’s life but long after it closes. Policymakers and investors must work closely with communities to ensure that the pursuit of economic gain does not come at the expense of water security, health, and future generations.

Although GoviEx claims that its processing plant will operate as a closed system with no liquid effluent, the groundwater or river contamination risk cannot be eliminated. The ecologically sensitive area supports thousands of livelihoods through fishing, tourism, and agriculture. If contamination were to occur, whether from a technical fault, human error, or regulatory oversight, the consequences could ripple across ecosystems and economies far beyond the mine’s boundaries.

Furthermore, uranium brings a specific set of environmental and health risks that Zambia has never had to manage at scale. Radiation exposure, even at low levels, requires rigorous monitoring. During an ESIA disclosure meeting held on 4 June 2025, representatives from African Mining Consultants, acting on behalf of GoviEx, noted that radiation exposure will primarily be limited to mine workers, who will be equipped with personal protective equipment (PPE) and subject to occupational safety protocols. While this reflects a proactive approach to worker protection, what happens when equipment fails? Who ensures radiation does not leach into water or soil over time? We must confront these questions honestly, not after the fact, but now.

GoviEx has submitted a draft Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the Muntanga Uranium Project to the Zambian Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA). This marks a critical regulatory milestone in the project’s transition from feasibility to execution. According to GoviEx, the agency is reviewing the submission and will provide feedback, which the company intends to incorporate into a final ESIA, expected in the second half of 2025.

Like many mining developments, the Muntanga Project will require resetting local communities, particularly around the Gwabi site. During the ESIA disclosure meeting, GoviEx, through its representatives, outlined commitments to provide compensation, improved housing, access to clean water and sanitation, and agricultural support. While these pledges are encouraging, their successful implementation depends on strong accountability mechanisms.

Yet, resettlement is not merely about replacing physical structures. Land is more than just space to live; it carries ancestral, cultural, and spiritual significance. Uprooting people from the land they have known for generations is not simply a technical process but a profound social and psychological rupture. Without sustained engagement and genuine respect for these deeper dimensions, even well-intentioned plans risk leaving communities fractured and vulnerable.

Further feedback revealed more concerns. Stakeholders, including tour operators and affected local communities, questioned the transparency of the process and whether communities, particularly those in Chiawa, were sufficiently consulted. Others questioned GoviEx’s operational experience, highlighting that it will be their first time mining uranium. These are not trivial concerns. Community trust and regulatory clarity are essential for a project of this magnitude. If people do not feel heard, the project risks sparking long-term resentment, even conflict.

Regulatory oversight emerged as a key area of concern. Institutions such as the Zambia Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA) and the Water Resources Management Authority (WARMA) are central to ensuring that environmental and social safeguards are upheld throughout the project’s life. However, as of the disclosure meeting, the extent and clarity of their involvement remained uncertain. This raises important questions: Are these institutions sufficiently resourced and equipped to manage the complexities of uranium mining? Do they have access to the necessary technical expertise to monitor radiation, oversee closed-system waste controls, and enforce long-term land rehabilitation? Ensuring robust oversight will require clear institutional roles and investments in capacity building and independent monitoring. Even with strong intentions, outcomes may fall short without the systems and support to back them.

Beyond the technical and regulatory dimensions lies a deeper moral and developmental question: Who benefits? The mine promises jobs, but how many will go to residents? How many will be skilled, long-term positions, and how many short-term or outsourced? What portion of the mine’s revenue will be reinvested in community development, education, health services, or environmental restoration? These are not questions posed in opposition to development but in service of more inclusive, accountable growth.

Uranium mining is not inherently bad. It can support low-carbon energy generation and deliver long-term economic returns when done responsibly. However, responsibility goes far beyond submitting an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). It means engaging communities from the start, maintaining complete transparency around environmental data, giving civil society a meaningful seat at the table, and ensuring that the benefits of extraction do not bypass those whose lives and landscapes are most directly affected.

Zambia has an opportunity to lead. As global demand for critical minerals grows and more countries turn to Africa, we can demonstrate that development and dignity can go hand in hand. But this requires the courage to demand more from investors, regulators, and ourselves. Environmental justice, social inclusion, and transparent governance must not be treated as lofty ideals but practical, enforceable standards.

To that end, several actions are essential:

- Independent Review – Commission an independent review of the ESIA to assess the project’s environmental and social risks comprehensively.

- Community Consultation – Facilitate meaningful, inclusive consultations with local communities to understand their priorities and integrate their input into project planning.

- Strengthen Regulations – Advocate for robust, enforceable environmental and social safeguards for uranium mining.

- Alternative Development – Explore and invest in alternative, community-driven economic development pathways that promote sustainability beyond resource extraction.

The Muntanga Uranium Project is more than just a mine. It is a test of whether Zambia can move beyond extractive models of the past and chart a course toward a future that is sustainable, equitable, and sovereign. We must choose carefully. Once the ground is broken and the ore is gone, what remains must still be worth calling home.

0 Comments